As we looked at the straggly bushes in our neighbor’s garden, we wondered if we’d mistakenly assumed he’d tidy his garden when we, his new neighbors, moved in. A few days later, he happened to walk past when we were again assessing the bushes after a walk. We introduced ourselves, and his face lit up as his eyes followed ours. ‘You’re in for a real treat come mid-October,’ he enthused. ‘I won’t be here, as I’m heading to the Amazon to take a group bird watching, but you’ll be witness to an amazing sight!’ He then explained that as an ornithologist, his time in the Amazon had to coincide with when specific birds were visible. But it also coincided with the annual arrival of the Migratory Monarch Butterflies in Texas, traveling from northern and central USA to their winter home in Central Mexico. In our kind and smart neighbor’s absence, they’d still be assured of ample food supplied by the straggly milkweed bushes. Although we’d seen a documentary on these fascinatingly resilient butterflies, we’d never imagined that we would eagerly await their arrival in a few weeks. But the story doesn’t end here.

E O Wilson was a Harvard University Biologist who believed that humans have an ‘innate tendency to focus on life and lifelike processes, an urge to affiliate with other forms of life.’ He suggested that the urge was powerful and that our thinking and well-being are negatively impacted when this urge is suppressed, as it is now, where non-living materials surround us. This phenomenon was termed ‘biophilia’ by Erich Fromm initially and later used prolifically by Wilson.

If Fromm and Wilson are correct, could it be in our genes to love green spaces? Could we be genetically primed to feel at home in and love, natural environments?

Marc Berman, along with other researchers, has examined and worked on defining ‘naturalness,’ and has found a few defining characteristics that natural landscapes share:

- They feature less variation in colour or shade than in urban settings. i.e., the colour range of such environments ranges from greens, to yellows, to browns and more greens.

- However, these colours are also more saturated and undiluted.

- Natural landscapes contain more curving shapes and fewer straight lines.

- Natural environments also contain different types of light, which changes depending on a variety of factors, such as the movement of light on leaves or water.

- Sounds are part of nature, too – they form part of its backdrop, such as wind whispering through trees, birdsong, or ocean waves.

The human brain likes order, but …

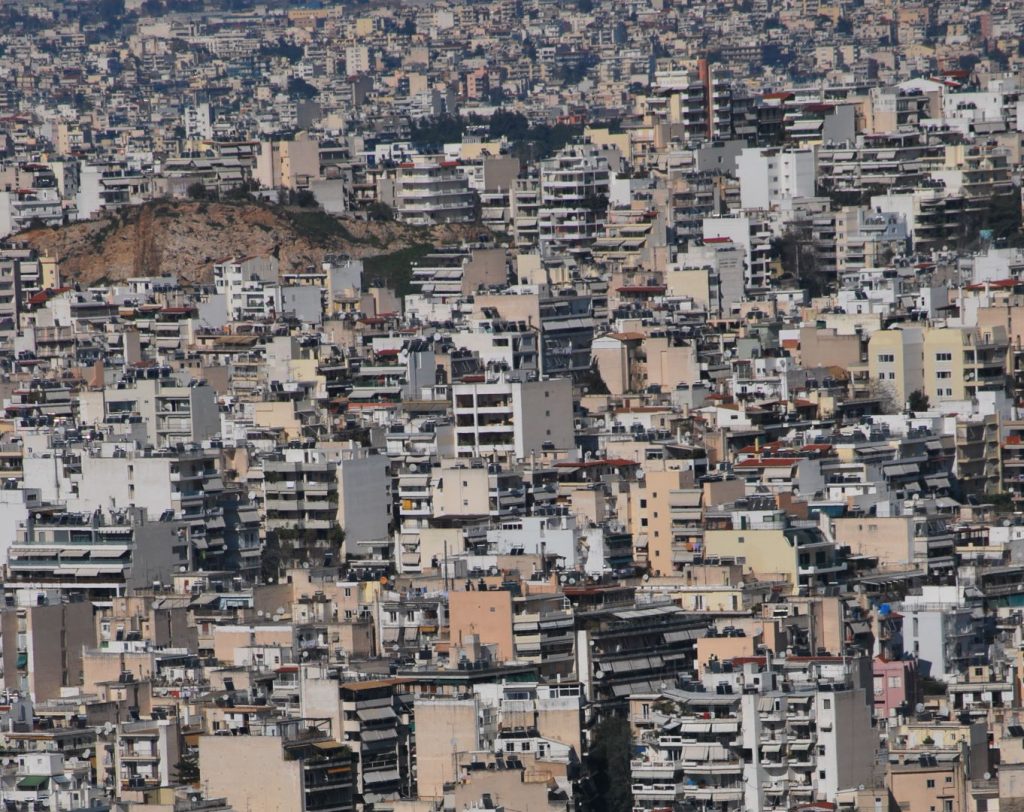

Research suggests that we prefer orderly environments to the opposite, but nature is naturally more disorderly, and yet we prefer nature to man-made environments. This is called the ‘nature-disorder‘ paradox. It seems that the extra visual information and variety that nature provides our visual system is what humans crave – and enjoy more – than what we’ve created. Although more orderly, such man-made environments don’t appeal in the same way.

And the extra visual information in nature appeals to the abundance of visual capacity we have available cognitively. About a third of the neurons in our cortex is dedicated to visual processing. However, instead of being exhausting, the extra visual stimulation that the visually complex and nuanced scenes in nature provide is what the brain favours versus urban environments that may be more orderly but are less appealing.

Yannick Joye and her colleagues have been researching how we feel in nature and why and uses the words ‘perceptual fluency’ to describe how nature makes us feel. Apparently, being in nature gives our brains a rest and provides us with positive emotions because we can absorb information without mental effort.

The natural curves, few straight lines, and myriad shades of colours, accompanied by different light and sounds in natural settings, are perceived to be more coherent by our senses compared to man-made settings. The predictability of what we sense we’ll see next in nature is comforting and contrasts starkly with what we can’t anticipate we’ll see next in man-made environments. For example, the sharp corners in shopping centers leave us apprehensive about what could be around the corner. The fact that we regularly navigate these environments now doesn’t mean our senses are at ease doing so.

Want to ‘blind’ your brain?

Another aspect of modern life is much repetition, or ‘sameness.’ When we see too many similar items, for example, hundreds of cereal boxes, our brain employs something researchers call ‘repetition blindness.’ Confronted by “sameness,” our brain naturally looks for differences, but when it can’t find enough variations, it blends everything together, becoming “blind” to the individual items or packages themselves.

Nature offers the opposite because there are seldom too many of the same items available for view. The constant change and shifting of items within natural environments allow for the sense of continuity and comfort we experience when in nature. The phrase ‘soft focus’ can be used to define what our brain does when we’re looking at nature – our brain is softly, gently engaged, without feeling a need to focus on any one thing specifically. It’s not searching for patterns as it’s engaged with perceiving subtle, ever-changing, natural phenomena.

Hidden, natural, and powerful patterns

However, this doesn’t mean that we don’t gravitate to patterns within nature, as scientists who study a specific form of patterns are quick to tell us. Fractals are non-regular geometric shapes with the same degree of non-regularity on all scales. Think of a fractal as a never-ending pattern that can occur anywhere in nature. The most common example of a fractal is the frond of a fern, where each segment of the fern is the same shape despite differing in size. Fractals are found in clouds, flames, mountain ranges, sand dunes, and waves, to name a few. They illustrate clearly that nature isn’t disordered, and our brains gravitate to these fractal patterns.

Although we do find fractal patterns in man-made environments, they are more common in nature, and our brains prefer the ones that are embedded in nature. Scientists have ranked fractal patterns according to their complexity and have found that those found in nature can be categorized in the middle range, with values between 1.3 and 1.5. Research has shown that exposing people to fractals within this range had a soothing effect on their Central Nervous system (CNS). A state termed ‘wakefully relaxed’ is used to explain this ‘fractally-induced’ state of relaxation.

These special, natural patterns may also enhance our ability to problem solve and think clearly, some research suggests, as exposure to fractals led to participants solving puzzles more accurately, easily, and quickly in Joye’s research.

Nature and healing

Roger Ulrich, an environmental psychologist, turned professor of architecture, showed decades ago that exposure to nature, via a view of greenery, promoted healing and relieved pain among patients who’d recently undergone surgery. His own experience with illness as a child led him to examine whether his positive experience of seeing the trees in the wind would have the same effect on hospital patients. Ulrich believed we should ‘exploit nature like a drug’ due to its powerful impact on physical health, healing, and the patient’s state of mind.

‘Exploit nature like a drug.’

Roger Ulrich

Further research has confirmed what Ulrich felt from personal experience and what he saw happen to hospital patients. Exposure to nature does indeed impact healing and pain positively, probably due to a variety of physiological changes, such as:

- Brain activity becomes more relaxed, which lowers cortisol synthesis

- Blood pressure drops, which reduces the risk of CVD conditions

- Eye movements change, with a reduction in blinking and less frequent focus shifting

- Dopamine release is stimulated due to increased experience of pleasure

Forest Bathing, or Shinrin-yoku

In 1982 the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries defined Forest Bathing as ‘making contact with and taking in the atmosphere of the forest.’ Field experiments conducted in 24 forests across Japan revealed similar physiological effects to Ulrich’s research. Immersion in forest environments led to lower concentrations of cortisol, a stress hormone, lower pulse rate, lower blood pressure, and greater parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) activity. PNS activity switches on the ‘rest and digest’ part of our CNS. The participants who were immersed in an urban environment did not experience these positive effects.

Can nature make us smarter?

Marc Berman, the researcher mentioned earlier, who has collaborated on the taxonomy of what makes nature natural, has examined the cognitive benefits of interacting with nature with other researchers. ‘Attention restoration theory (ART) provides researchers with an analysis of the kinds of environments that lead to improvements in what they term ‘directed-attention’ abilities. Their research revealed that walking in nature does improve such cognitive abilities as measured with tasks that assess attention restoration.

Further research by these collaborators suggests that ‘cognitive tasks that involve working memory and cognitive flexibility may improve most reliably after nature exposure, while tasks that require attentional control show some improvements.’

Does being in nature improve creativity?

Within our brain, we have several neural networks that perform a variety of functions. One of these networks is the ‘default mode network’ or DMN. The DMN is defined as a network of interconnecting brain regions activated when we are, ironically, not actively focused on the outside world. The ‘soft focus’ effect mentioned previously engages the DMN, and researchers suspect this allows the brain to loosely associate aspects of our environment with our thoughts, ideas, and memories. This mental state can usher in creativity because our brain becomes susceptible to connections and associations that don’t appear when we’re actively focused on something.

It’s likely that a combination of improved mood, stress reduction, and the lack of forced focus yield a unique creative state that allows the brain to be more open-minded and take advantage of the variety of inputs and thoughts that occur in such a state.

Can we bring nature inside? And is it useful?

Ruth Raanaas and fellow researchers asked this question about attention in an office setting. They discovered that there was an improvement in the attention capacity of those office workers exposed to plants, which suggests that executive activity (located in the prefrontal cortex – PFC brain region) is improved in the presence of plants. A recent meta-analysis confirmed cognitive benefits along with physiological ones, such as reduced blood pressure, among people exposed to indoor plants.

We’re already aware of how crucial direct light is to our physical health in the form of vitamin D and the effects of low light on mood, manifesting as Seasonal Affective Disorder, aptly acronymic as SADs. It shouldn’t come as a surprise that a small study revealed that exposure to natural light improved sleep, which positively affects overall health and well-being. In another small study, subjective reports of eyestrain, headaches, lighting quality satisfaction, window glass lighting quality, and alertness were significantly better for employees in electrochromic glass buildings compared to those in buildings with low natural light exposure.

Google took this research on board and tested it seven years ago, along with introducing plants to the workplace, and self-report results showed deeper focus and increased creativity with more light and plants in workspaces.

‘Greenness’ Inside Schools

School students taught how to create a ‘green wall’ in their classrooms may experience the same benefits, as revealed by a small study by researchers interested in the interaction between learning and design. They hypothesized that as humans respond more positively to a natural versus a built environment, installing a ‘green wall’ would lead to improved attention and reduced stress levels. Another study also showed positive benefits, including fewer sick days among students learning in a ‘green wall’ classroom and a positive rating of ‘green wall’ classrooms compared to those without natural greenery.

What about ‘greenness’ outside schools?

Research suggests that students exposed to ‘greenness’ outside of their school perform better academically, as measured by English and mathematics results than students exposed to less verdant surroundings. The amount of green land surrounding the schools in the study was used as the metric to compare the academic results, and confounding variables such as socioeconomic status were accounted for. Researchers even took the season into account, which impacted how much ‘greenness’ was available, and Leung and colleagues stated that ‘Students with healthier mental and physical conditions are more motivated, and are capable of learning, which makes them perform better.’

Li D et al’s research explains the improved cognition among students exposed to ‘greenness’, suggesting it occurs because natural landscapes relieve mental fatigue and stress, which would naturally lead to improved cognition.

Young adults benefit too.

Researchers who were curious about the effects of nature on attention among two groups of university students decided to assess the effects of a 40 second view of a city scene with a flowering meadow green roof or a bare concrete roof. Participants who viewed the green roof made significantly lower omission errors while also showing more consistent responses to the task when compared to the concrete roof viewing participants. The researchers suggest that these nature-micro breaks impact cortical regions responsible for attention.

But what about nature and mood?

A systematic review and meta-analysis in which 50 studies were examined that assessed nature-based outdoor activities for mental and physical health found that ‘The most effective interventions were offered for between 8 and 12 weeks, with the optimal dose ranging from 20 to 90 min.’ The researchers found that gardening, green exercise, and nature-based therapy were all effective at improving mental health outcomes in adults, including those with pre-existing mental health problems.

Supporting the ‘dose response’ hypothesis, researchers who analyzed data from close to 20,000 participants found that spending at least 120 minutes a week in nature was associated with good health and well-being.

Although some research suggests that simulated natural settings can promote health via specific mechanisms, a meta-analysis of experimental data revealed that positive affect improved in actual, natural settings, not simulated settings.

It stands to reason then, that nature contact should be considered a firstline of defence for mental illness and overall brain health.

‘Nature is not only nice to have, it’s a have-to-have for physical health and cognitive functioning.’

Richard Louv

What’s all the fuss about ‘Awe?’

Apart from these physiological, cognitive, and psychological benefits that being exposed to nature and ‘greenness’ provide, another psychological effect has become well known: that of ‘awe.’ Awe is defined as ‘a feeling of reverential respect mixed with fear or wonder.’ A professor of psychology at the University of California, Dacher Keltner, defines awe further by calling it an emotion ‘in the upper reaches of pleasure and on the boundary of fear.’

Experiencing awe provides us with several benefits, such as radically shifting our perspective, increasing our curiosity and open-mindedness, and our boundaries, or the capacity to separate ourselves from others using stereotypes. This shift allows us to feel more connected to humanity, which spurs altruistic behavior. It seems that seeing ourselves in perspective, seeing ourselves as small in comparison to nature and what it encompasses, invokes a sense of connectedness with other living beings that nothing we encounter in our man-made world can do.

A specific type of awe experienced by very few people is called the ‘overview effect’ and refers to the emotion astronauts experience when they look at earth from space. Alan Shepherd, who walked on the moon in 1971, said, “when I first looked back at earth, standing on the moon, I cried.” Researchers who study this effect suggest that it stems from seeing the earth’s beauty and fragility, coupled with a dissolution of the boundaries that separate us on earth.

‘Awe is an emotion in the upper reaches of pleasure and on the boundary of fear.’

Dacher Keltner

‘Awe’ can make us nicer people.

According to researchers, it can. Indeed, a simple experiment supports their suggestion. A group of students who were directed to look at large trees exhibited more pro-social behavior in the form of helping the experimenter pick up ‘accidentally’ dropped pens compared to those who had observed versus a large building. According to the researchers, these findings suggest that awe may be a powerful trigger of prosocial behavior.

Jonathan Haidt, one of my favorite authors, who examined ‘awe’ with Keltner years ago, suggests in his book ‘The Righteous Mind,’ that ‘awe’ could be a ‘reset button’ for the human brain.

However, it’s not one we can access simply to ‘re-set.’ We need to go out into nature, to look at what is so much larger than us, to incite a sense of awe. We won’t get it by looking at our TVs or devices. We need to search for it.

How are time and nature related?

Researchers with a sense of humor and knowledge of our current sense of time poverty, titled their published study ‘Time Grows on Trees.’ They discovered that time spent in nature is overestimated relative to actual time, whereas time spent in urban settings is correctly estimated. Study participants experienced improved mood and a reduction in stress, which the study authors associate with our slowed perception of time when we’re in nature. As time slows down, our brain feels happier and less stressed. Who doesn’t want these benefits in what feels like an increasingly time-poor world?

Although we’ve discussed some of nature’s physiological, cognitive, and emotional effects on our wellbeing, it’s impossible to separate them in reality. When our stress levels decline, our physical health improves. When our mood improves, our capacity to cope with life and stressful events improves, and we become more cognitively resilient. Put simply, the positive emotions brought about by spending time in green spaces have a positive effect on brain function.

‘We can’t separate nature’s physiological benefits from the psychological or cognitive benefits.’

Dr Delia McCabe

What happens when we’re deprived of nature?

The author of ‘The Nature Principle’ and ‘The Last Child in the Woods,’ Richard Louv, coined the term “nature-deficit disorder” to describe the generation of children deprived of the capacity to explore nature.

Parents and educators who have heeded his warning have incorporated nature into their school day, for example, The Butterfly Garden in Cedar Park, Texas, making nature the school itself. [I’m particularly drawn to the name of this school as the butterflies move happily between the straggly bushes in my neighbor’s garden.]

Although there is not yet a large body of longitudinal or randomized, controlled studies on the effects of nature on human beings, the studies that do exist suggest positive effects of nature exposure. Furthermore, there is very little research about how ‘nature deprivation’ impacts humans. However, some observational research suggests that people who move from urban areas to where there is more greenery experience increased mental well-being. Other research suggests that increased exposure to vegetation may suppress urban crime.

This research should be a wakeup call for all city dwellers.

‘Where we are shapes who we are.’

Roger Ulrich

How to incorporate more nature into our lives

Deep immersion, or the 3-Day effect

The ‘3-Day Effect’ refers to a book written by Florence Williams, quoting David Strayer (and including his research), who coined this term referring to what happens to us when we immerse ourselves in nature for at least this period of time. The science behind this effect suggests that living in the wild sans technology can make us happier, boost our creativity, increase our overall well-being and reduce our anxiety.

This effect seems to ‘kick in’ due to our new reality and increased clarity of thought. Strayer, who uses this phenomenon to jump-start his own creativity, believes that what we’re experiencing when we succumb to this effect is a state of deep rest for our busy PFC, which frees up our attentional network. A neural recalibration occurs, in which sensory perception and productive daydreaming (‘soft focus and DMN activity) occur.

‘Your new reality starts on the third day.’

David Strayer

Mini Nature breaks – choose green over screen

Even mini breaks in nature result in improved physiological and psychological effects, along with a reduction in stress, as illustrated in some of the preceding research. We already know that moving our body offers cognitive benefits but doing so in nature is a great way to maximize both benefits and our time. And remember, time seems to move slowly while we’re in nature due to the time-slowing effect nature exerts on our brain, which leaves us feeling less anxious and stressed. Furthermore, optimizing cognitive function is hampered when we’re stressed, so a min green break offers the opportunity to reduce stress levels naturally.

Bring nature into your home and workspace

Add more plants to your lived spaces to continue enjoying the benefits of being close to and gazing at green plants. And change your screensaver to one that shows a nature scene versus a man-made one. Then you naturally have a backdrop of nature on your screen as you work. As I type this article, I have the apple mac green grass screensaver as my backdrop.

‘Without a connection to nature, people lose interest in protecting it.’

Richard Louv

After all, why would one work to protect something one doesn’t value?’ While some groups of people work tirelessly globally to protect our increasingly fragile and evidentially struggling home, other groups of people are increasingly isolated – some willingly lured into electronically simulated environments – others by urban design that ignores our need for nature in our environment.

Still, others who feel ‘eco-anxiety,’ which is ‘the chronic fear of suffering an environmental cataclysm’ visit therapists like Stephanie Bednarek; a speaker, writer and consultant on climate psychology; who specializes in helping sufferers cope with what seems like insurmountable anxiety and sadness around the loss of nature.

An Australian environmental researcher and philosopher Glenn A. Albrecht used the term ‘solastalgia,’ to describe the distress and sadness we experience when we seek solace or comfort in a place that is being destroyed. He based this definition on the words solace (that which gives comfort) and algos (Greek for pain).

This brings me back to the butterflies.

These beautiful butterflies have a stopover of a few weeks, among what we now know are life-saving bushes. They’ve made this journey since long before etymologists started studying their migratory behavior, but these unique milk-weed spots have been disappearing in the wake of rampant urban development. Instead of millions, they’re now estimated to be in their thousands.

Gardeners like our insightful neighbor, who remember and understand their yearly pilgrimage, have ensured gardens waiting with their favorite ‘straggly’ bushes. Who will remember their journey when these gardeners are gone? When buildings entirely swamp their now tiny stop-overs? What will these beautiful butterflies do when they try to stop over but find no sustenance waiting for them?

We are losing our peace of mind and mental and physical well-being, as we neglect our home and precariously balanced ecosystems. We neglect the fragile web of nature that holds us all together. If enough of us make embracing and immersing ourselves in nature a priority, we will have a chance of saving ourselves and our beautiful planet. But we need to actively look for awe-inspiring experiences; we need to immerse ourselves in nature daily; we need to bring nature inside, not just into our homes, but back into our lives. We lose the best parts of ourselves when we deprive ourselves of nature. We’re also going to lose our only home.

About the author. Dr. Delia McCabe. Delia’s research has been published in several peer-reviewed journals, she is a regular featured expert in the media, and her two books, translated into four languages, are available internationally. Delia uses her psychology background, combined with nutritional neuroscience and neurological perspectives, to support behaviour change and stress resiliency within corporates.

References

Alcock I, et al. (2014) Longitudinal Effects on Mental Health of Moving to Greener and Less Green Urban Areas. Environ. Sci. Technol;48 (2):1247-1255.

Atchley RA, et al. (2012) Creativity in the Wild: Improving Creative Reasoning through Immersion in Natural Settings. PLoS ONE 7(12):e51474.

Barbiero G & Berto R (2021) Biophilia as Evolutionary Adaptation: An Onto- and Phylogenetic Framework for Biophilic Design. Front. Psychol;12:700709.

Barton J & Rogerson M (2017) The importance of greenspace for mental health. BJ Psych Int;14(4):79-81.

Berman MG, et al. (2008) The cognitive benefits of interacting with nature. Psychol Sci;19(12):1207-12.

Berman MG et al (2014) The Perception of Naturalness Correlates with Low-Level Visual Features of Environmental Scenes. PLoS ONE 9(12):e114572.

Boubekri M, et al. (2014) Impact of windows and daylight exposure on overall health and sleep quality of office workers: a case-control pilot study. J Clin Sleep Med;10(6):603-11.

Browning MHEM (2020) An Actual Natural Setting Improves Mood Better Than Its Virtual Counterpart: A Meta-Analysis of Experimental Data. Front. Psychol;11:2200.

Coventry PA, et al (2021) Nature-based outdoor activities for mental and physical health: Systematic review and meta-analysis, SSM – Population Health;16:100934,

Davydenko M & Peetz, J (2017) Time grows on trees: The effect of nature settings on time perception. Journal of Environmental Psychology;54:20-26.

FerraroIII FM (2015) Enhancement of Convergent Creativity Following a Multiday Wilderness Experience. Ecopsychology;7(1):7-11.

Frumkin H (2001) Beyond toxicity: human health and the natural environment. Am J Prev Med;20(3):234-40.

Goldfarb L & Treisman A (2011) Repetition blindness: The survival of the grouped. Psychon Bull Rev;18:1042-1049.

Hagerhall CM, et al (2015) Human physiological benefits of viewing nature: EEG responses to exact and statistical fractal patterns. Nonlinear Dynamics Psychol Life Sci;19(1):1-12.

Han KT, et al (2022) Effects of Indoor Plants on Human Functions: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analyses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health;19(12):7454.

Han, KT (2009) Influence of Limitedly Visible Leafy Indoor Plants on the Psychology, Behavior, and Health of Students at a Junior High School in Taiwan. Environment and Behavior;41(5):658-692.

Hedge, A (2018) Worker Reactions to Electrochromic and Low e Glass Office Windows, Ergonomics International Journal;2(4):1-12.

Joye Y, et al (2016). When complex is easy on the mind: Internal repetition of visual information in complex objects is a source of perceptual fluency. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform;42(1):103-14.

Kathryn JH, et al (2018) Conceptualising creativity benefits of nature experience: Attention restoration and mind wandering as complementary processes, Journal of Environmental Psychology;59: 36-45.

Keltner, D & Haidt, J (2003) Approaching awe, a moral, spiritual, and aesthetic emotion, Cognition and Emotion;17(2):97-314.

Korpela KM, et al (2018) Environmental Strategies of Affect Regulation and Their Associations With Subjective Well-Being. Front Psychol;18;9:562.

Kotabe HP, et al (2017) The nature-disorder paradox: A perceptual study on how nature is disorderly yet aesthetically preferred. J Exp Psychol Gen;146(8):1126-1142.

Lee KE, et al (2015) 40-second green roof views sustain attention: The role of micro-breaks in attention restoration, Journal of Environmental Psychology;42:182-189.

Leung WTV, et al (2019) How is environmental greenness related to students’ academic performance in English and Mathematics? Landscape and Urban Planning;181:118-124.

Li D, et al (2016) Impact of views to school landscapes on recovery from stress and mental fatigue. Landscape and Urban Planning;148:149-158.

McCullough MB, et al (2018) Implementing Green Walls in Schools. Frontiers in Psychology;9:619.

Murphy Paul, A. (2021) The Extended Mind: The Power of Thinking Outside the Brain. Harper Collins: USA.

Park BJ, et al (2010) The physiological effects of Shinrin-yoku (taking in the forest atmosphere or forest bathing): evidence from field experiments in 24 forests across Japan. Environ Health Prev Med;15:18-26.

Pradeep, AK (2012) The Buying Brain. John Wiley: USA.

Raanaas RK, et al (2011) Benefits of indoor plants on attention capacity in an office setting, Journal of Environmental Psychology;31(1):99-105.

Rojas-Rueda D, et al (2019) Green spaces and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. The Lancet Planetary Health, Elsevier;3(11):E469-477.

Schertz KE & Berman MG (2019) Understanding Nature and Its Cognitive Benefits. Current Directions in Psychological Science;28(5):496-502.

Seymour V (2016) The Human-Nature Relationship and Its Impact on Health: A Critical Review. Front. Public Health;4:260.

Stevenson MP, et al (2018) Attention Restoration Theory II: a systematic review to clarify attention processes affected by exposure to natural environments. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev;21(4):227-268.

Taylor RR (2006) Reduction of Physiological Stress Using Fractal Art and Architecture. Leonardo;39(3):245-251.

Ulrich RS, et al (1991) Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J Envir Psychol;1991;11:201-30.

Ulrich, RS (1981) Natural Versus Urban Scenes: Some Psychophysiological Effects. Environment and Behavior;13(5):523-556.

White MP, et al (2019) Spending at least 120 minutes a week in nature is associated with good health and wellbeing. Sci Rep;9:7730.

Wolfe MK & Mennis J (2012) Does vegetation encourage or suppress urban crime? Evidence from Philadelphia, PA, Landscape and Urban Planning;108(2-4):112-122.

Yaden DB, et al (2016) The overview effect: Awe and self-transcendent experience in space flight. Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice;3(1):1-11.

Joye Y & van den Berg A (2011) Is love for green in our genes? A critical analysis of evolutionary assumptions in restorative environments research, Urban Forestry & Urban Greening;10(4):261-268,

https://tocaboca.com/magazine/nature-deficit-disorder/ Cited 25th October, 2022

https://frankwhiteauthor.com/ Cited 25th October, 2022

https://e360.yale.edu/features/ecopsychology-how-immersion-in-nature-benefits-your-health Cited 25th October, 2022